By Jeremy Cook

A multi-day music festival hosted south of Warwick found itself at the centre of an unprecedented free and legal drug testing initiative over the Easter long weekend.

Taking over Cherrabah Resort for five days, the Rabbits Eat Lettuce festival hosted Queensland’s first event-based pill testing service.

Though the initiative had previously been trialled on several occasions at music festivals in other parts of Australia, the weekend’s festival was the first time the service had been offered at an event running for more than one day.

Two festival goers in their 20s were found dead inside a tent in 2019, when the festival was last held at Cherrabah, after taking a lethal concoction of drugs.

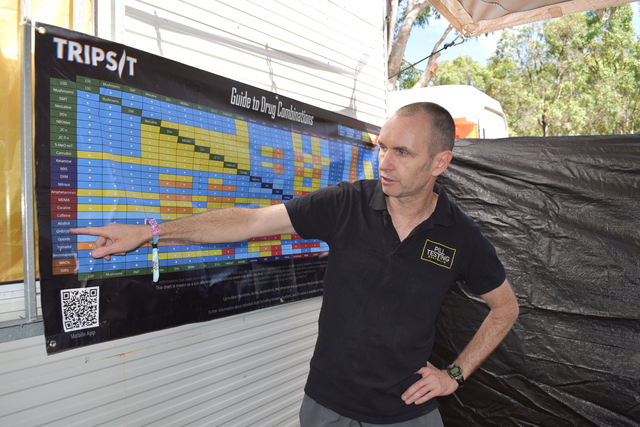

ANU professor Malcolm McLeod was on site at the festival to explain how the service works. As lead chemist for Pill Testing Australia, the harm reduction organisation delivering the service, Professor McLeod said he was confident pill testing could save lives.

“We know from events in some of the southern states recently that unfortunately drug use at festivals does occur and it can have tragic consequences,” Professor McLeod said.

“Pill testing allows us to get ahead of that to test the drugs before people take them and hopefully educate them a little bit about what they’re taking and how they can be safer,” he said.

“We saw in the recent spate of overdoses in Melbourne that most of those clients expected to take MDMA but they also had other drugs on board [bath salts] that we know we can detect.”

Professor McLeod said the free service available to anyone and would remain open for six hours a day on most days of the event.

Chemical analyst and Pill Testing Australia volunteer Blake Curtis said chemists would test whatever substances they were presented with by analysing the “fingerprint” of the drug against a library of more than 30,000 other fingerprints to determine what substances were present.

If a harmful substance is detected or the drug is not what was expected, users can choose to discard the substance at the pill testing site.

Where trials have previously taken place at festivals such as Spilt Milk and Groovin The Moo in Canberra, Professor McLeod said about 10 to 15 per cent of samples were usually discarded.

“On occasion we do find drugs that are not what the client expects, they’re adulterated with other substances or they’re substituted for other substances and these might be of greater risk if you don’t know a lot about their effects and how they interact with the client,” he said.

“We have a direct line to the festival organisers so should we find something of serious concern then I’m sure that they would be able to take steps and alert the clients.

“In past festival services we’ve interacted with medical services, we’ve even tested substances that have been surrendered by patients who end up in the medical service in need of some attention, and we’ve been able to identify the substances which might aid in their treatment.”

In addition to testing substances, harm reduction workers were also onsite to inform festival goers on the risks associated with drug consumption.

Hung up on the walls of the site’s waiting area were charts displaying information on drugs typically found in recreational settings and how lethal they could be when combined with other substances.

The initiative’s introduction at Rabbits Eat Lettuce formed part of a state government commitment, announced a little more than a week before the festival was due to start, to invest almost $1 million in delivering pill testing services over the next two years.

Festival goer Lee said introduction of pill testing was “well overdue” and would help people make more informed choices.

“I think it’s so useful, so needed,” she said.

“I’ve travelled and been to festivals in other countries where that’s a service that’s available [and] I think it makes for a much safer partying environment.

“There’s definitely people who if they knew there was something that shouldn’t be in what they were planning to take, they’re not going to take it, or they’re not going to pass it on or share that with their friends.”

The identities of users remain confidential when interacting with the service which also goes unpoliced.

Speaking prior to the event, Warwick Acting Police Inspector Jamie Deacon said he was “fully supportive” of health initiatives which target harm reduction.

Though he said police would still be conducting enforcement activities for people entering and exiting the event itself.

“If people are going to take those drugs, then people need to know they’re safe,” Acting Inspector Deacon said.

“We will still do what we do …, knowing that drugs and music festivals somewhat go hand in hand.”

UQ researchers are expected to evaluate pill testing services rolled out by the state government under the two-year initiative and develop a state-wide monitoring framework for future testing regimes.