By ROBERT MACMAURICE

PROBABLY the first European person to meet a Kambuwal person (Gambuwal and other variations of spelling are also documented) was Allan Cunningham on 13 June 1827.

He described it in his journal in the following way:

“Although very recent traces of natives were remarked in different parts of the vale, in which we remained encamped about a week, only a solitary Aborigine (a man of ordinary stature) was seen, who in wandering forth from his retreat in quest of food chanced to pass the tents. Immediately however, upon an attempt of one of my people to approach him, he retired in great alarm to the adjacent brushes, at the foot of the boundary hills, and instantly disappeared. It therefore seems probable that he had not previously seen white men, and possibly might never have had any communication with the natives inhabiting the country on the eastern side of the Dividing range, from whom he could have acquired such information of the existence of a body of white strangers on the banks of the Brisbane, and their friendly dispositions toward his countrymen as might have induced him to have met with confidence our overtures to effect an amicable communication…”.

That person would have been a Kambuwal tribal member. What he reported to others would also have been interesting for the historical record.

The Kambuwal people lived in an area of 9600 square kilometres, from Bonshaw, Inglewood, Millmerran, Leyburn, east of Stanthorpe, the western slopes of the Great Dividing ranges, and Tenterfield.

The Kambuwal people were surrounded by other peoples including the Jukambul, Ngarabal, Kwiambal, Bigambul, Giabel, Keinjen, and Kitabal. Crossing the borders of tribal lands, without permission, could lead to punishment of the infringer.

Allan Cunningham and his party of six men and 11 horses, in all innocence, had to cross many tribal boundaries in his 1827 journey from Sydney to his discovery of the Darling Downs and back. During the 14-week journey he only observed Aborigines on five occasions. Perhaps the strangeness of these white people held the landowners back.

It was Allan Cunningham’s discoveries that led to many other people arriving on the Darling Downs eager to claim land. The fact that Aboriginal people had lived in this land for thousands of years was of no concern to them.

In early 1840, Patrick Leslie and a convict companion known as Murphy, were possibly the second Europeans to be sighted by the Kambuwal people, when they traversed a number of tribal lands. Patrick Leslie followed the same western pathway from Sydney, as did Allan Cunningham, and then criss-crossed the Southern Downs area looking for his ideal piece of land. The land that he took up was to become known as Toolburra Station and Canning Downs Station, which he stocked with sheep in late 1840, and later he acquired Goomburra Station in 1847. This was the land of the Keinjin people.

Patrick Leslie was noted as a “hard” man and he did not have good relations with the local Aborigines.

On one occasion he was attacked by Kambuwal people, who wished to murder him, but ironically was saved by some Keinjin people who were working as stockmen on his property. The reason for the Kambuwal attack was that a number of Kambuwal women had been raped by one of Patrick Leslie’s workers.

The next European that encountered the Kambuwal people was Matthew Henry Marsh and his three companions who came up from Sydney through the New England plateau. They camped at the present site of Maryland Station on 17 January 1842. In exploring the area around The Summit through to present-day Stanthorpe they became aware of about 500 Aboriginals in the area. These Aboriginals would have been Kambuwal people.

In another camp near the present Stanthorpe township the four men spent a fearful night, when they saw numerous fireflies, which they fearfully imagined as Kambuwal people coming to attack them. In daylight they recognised their mistake and as a result named the place Funker’s Gap, which is still the place name today. Funk being an old-fashioned term meaning panic or to be terrified.

Fear was probably the main emotion that Europeans experienced with Kambuwal people and other Aborigines. This fear led to atrocities, but for every European who died many more Aboriginals died in revenge.

Some estimates put the number of Kambuwal people at around 1500 at the time of European invasion. These numbers appear to have rapidly declined, as occurred in other tribes as well, with the presence of Europeans.

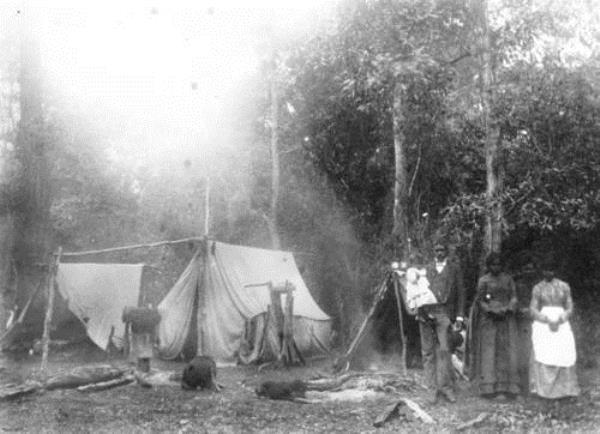

In the 1850s for instance, at the Golden Fleece Tavern, which was located where the township of Stanthorpe is now, there were reports of regular encampments of about 300 Kambuwal people on Quart Pot Creek. By the time of tin discovery and the formation of Stanthorpe in 1872, this was no longer the case.

In 1874 the then 14-year-old George Bamberry, who lived at Wylie Creek, discovered a Bora ring about two kilometres east of Ruby Creek. It was apparently last used by the Kambuwal people about 1873. Other Bora rings exist in the region.

About 100 Kambuwal words and a few expressions were recorded by Mrs Harriott Barlow during the 1850s and 1860s. “Wallangarra” meaning, long water hole and “Yandilla” a small town to the east of Millmerran, meaning running water, are two examples of surviving Kambuwal language. Other surviving traces of the Kambuwal people include stone implements and particular sites known to have been significant to them.

Kambuwal people were relocated as far away as missions on Fraser Island, and perhaps Cherbourg and Deebing Creek Mission (near Ipswich), with the break-up of their social and cultural living patterns. How many descendants are there today?

Beyond this the Kambuwal people and their knowledge and customs appear to have disappeared. Lost because of fear and the insatiable pursuit of land and fortune that the first Europeans saw in this land of opportunity.