The Great War of 1914 to 1918 produced many outstanding acts of bravery from the Anzac forces in the muddy, disease-ridden trenches of France and Belgium.

However, it could be argued that the Regiment’s stretcher bearers could claim that honour.

Research shows that a stretcher bearer was the first link in the evacuation process for wounded ‘Diggers’.

Many came from non-combatant ranks such as bandsmen, conscientious objectors of just volunteers, and usually, there were 16 of them placed in a battalion, and could number two, or up to six or even eight, and worked behind the advancing line of infantry.

They had to operate in the most trying conditions and were unarmed, but this did not make them immune to the incessant artillery shelling, machine guns and sniper fire.

As one stretcher bearer commented after the second battle of Ypres in 1917:

“Bringing the wounded down from the front line today. Conditions terrible. Ground is a quagmire. It requires six men to every stretcher; the mud in some cases is up to our waists”.

It was under these atrocious conditions that Private Alfred Cecil Benecke worked tirelessly as a stretcher bearer and demonstrated outstanding bravery under fire. For this, he was awarded the Military Medal. Here is Alfred’s story.

Alfred Cecil Benecke was born at Evergreen, via Kulpi, on 23 January 1895 as one of 11 children to Friedrich and Anna Benecke.

Evergreen is a small rural town and locality in the Toowoomba region, where the Oakey-Cooyar road runs right through it. In 1918 it had a population of 77 citizens.

He came from a large family of 11 children who all attended the Evergreen State School so it meant that all were involved in the farm work to assist the family in these tough times. After finishing school, Alfred, like many young men at this time, worked on the family farm until the clouds of war began to gather over Europe, which resulted in the nation’s call to arms to assist the mother country in 1914.

At the age of 21, Alfred decided to enlist so he travelled to the recruiting office in Toowoomba and enlisted into the Australian Imperial Force on 4 May 1916. He was seconded to the 52nd Battalion, 6th Reinforcements, and was sent to Fraser’s Paddock, Enoggera, Brisbane, for military training. On completion of training, Alfred was sent to Sydney and embarked on board HMAT A40 “Ceramic” on 7 October 1916 arriving at Plymouth, England, on 21 November 1916.

Alfred had to spend a week in the Military hospital at Codford with a slight illness, and after his discharge, he was transferred to the 47th Battalion at Estaples on 7 March 1917 and soon after, left Folkstone on board the SS “Invicta” for the Western Front in France. His Regiment was immediately into action as they joined the allied push towards the Somme. It was here that Alfred volunteered to be a stretcher bearer as the battle at Ypres was causing heavy casualties. Alfred received a minor wound but recovered, and was soon back on the advance with the battalion.

Alfred, now working as a stretcher bearer, was showing out as a very brave soldier as he went out from the trenches amid shell fire and machine guns to attend to the wounded and it was here in the heat of battle that Alfred’s finest hour came about that saw him awarded the Military Medal for his actions on the night of 28 September 1917. Here is how his recommendation came about:

“North of Polygon Wood on the night of 28/29 September. 1917, acting as a stretcher bearer, went out with a working party when they came under heavy machine gun and artillery fire. One of Private Benecke’s comrades became a casualty so, Benecke dressed him and assisted him to the Regimental Aid Post. He then returned to the party and later dressed and carried two men of the relieving Battalion to the RAP who had been wounded. It was necessary for him to remain behind from his unit to do this. The shell fire was heavy all the time. His unselfishness and brave actions greatly strengthened his comrades”.

As the Battalion continued to advance towards the Somme, Alfred continued to work as a stretcher bearer until the heavy battle that took place at Dernacourt, and in the aftermath, Alfred was reported as unofficially missing on 5 April 1918.

Unbeknown to his commanders, Alfred and his working party were captured by the Germans and it only became official when the Command in France received a cable from Melbourne, that they had been captured and were now on the official list of those missing in action were in German Internment camps. Apparently, the Red Cross, possibly informed Alfred’s next of kin that he was now a prisoner.

It was further established at an inquiry at Hurdcotte when a Corporal Holznagel (AIF) witnessed the capture, when he told the inquiry that Alfred and his party who were surrounded by German infantry, were told by their Officer Commanding to: “Run for your life or surrender”.

Alfred took the option to surrender and spent the last months of the war in a POW camp in Germany until he was repatriated back to Dover, England, from where he was held at Calais, on 11 December 1918.

Over 400 Anzacs were captured during the Battle at Ypres and Dernacourt and after the Armistice was signed on 11 November 1918, almost 264,000 allied military were repatriated back to their own countries. It is possible that Alfred was sent to many of the German POW camps to work behind German Lines somewhere in France.

Dover, in Kent, is just across the sea from France, and was a major ferry point for repatriated Australians at war’s end in 1918, which could possibly be where many came back to after their release.

As mentioned at the start of Alfred’s story, trench warfare on the Western Front was a terrible battlefield and caused many casualties, not only from the enemy’s bullets but also from the sticky mud and diseases that permeated the trenches. Such conditions as trench feet, typhoid fever, gangrene, chest infections, gas etc., which made it so hard to fight a war such as World War I. The incessant shelling and German pill boxes containing deadly repetitious machine gun fire made the battlefields so dangerous which helps to explain the 49,000 Australian deaths in this four-year conflict.

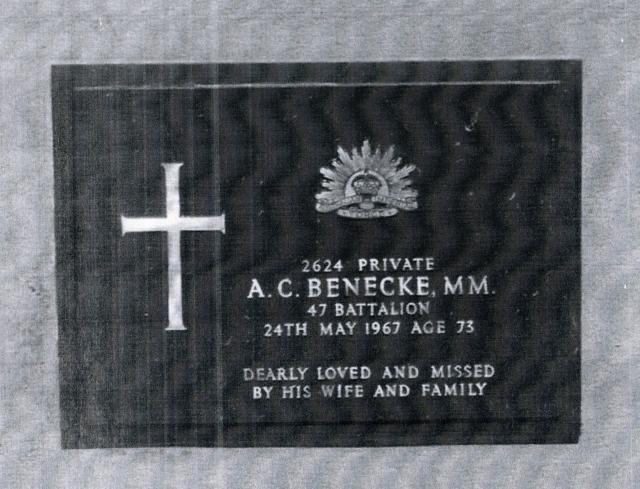

With his repatriation back to England from German internment on 11 December 1918, three months later, after health was regained, Alfred embarked from Liverpool on board the HMAT “Khyber” on 31 March 1919, and arrived in Brisbane on 18 May 1919. He returned to the farm at Evergreen and resumed life as a farmer, and on 19 July 1922 he married Bertha Spies, together they raised two sons and four daughters, and worked at Evergreen until his death on 24 May 1967. He now lies at rest in Evergreen Cemetery, Section 1, Row 5, Plot 0056.

Alfred Cecil Benecke was a great soldier and a very brave man for his actions in France. His work as a stretcher bearer enabled him to show all the hallmarks of the legendary Anzac. His great courage and mateship shown by his Military Medal award where he would not leave wounded comrades on the battlefield, was probably the reason he was captured.

Just to survive the horrors of trench warfare on the Western Front is a legacy in itself, and he did that with such nobility and courage, in one of the most dangerous battlefields of World War I.

Private Alfred Benecke, we salute you.