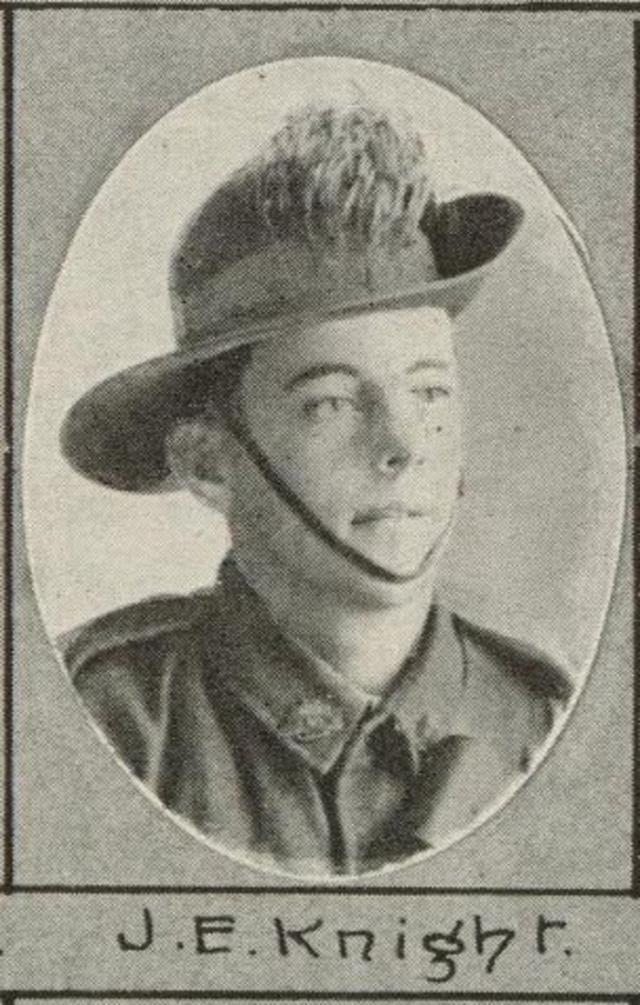

More info found on Yangan soldier James Knight

Digital Edition

Subscribe

Get an all ACCESS PASS to the News and your Digital Edition with an online subscription

Renewed scrutiny over controversial water licence

Despite persistent community opposition, Queensland Water Minister Ann Leahy has so far resisted making a call on whether to call-in and reassess the controversial...