Digital Edition

Subscribe

Get an all ACCESS PASS to the News and your Digital Edition with an online subscription

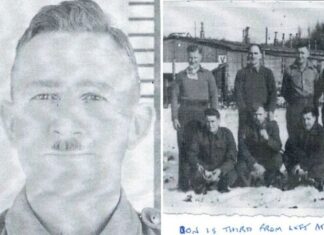

The untold story of a Warwick hero

The city of Warwick on the Darling Downs has a proud military history that encompasses the Boer War and both World War 1 and...