In 1916, World War I was raging.

Glen Aplin boy Claude Wandsworth Hughes followed his three older brothers into the war, enlisting on 1 August 1916 at only 17 years old though he stated he was 18 years and four months old.

It was reported in the newspaper that “the Hughes family of Glen Aplin, this week put up a record for they are doing their bit in the war, and district by the enlistment of the fourth son. Previously three sons – Messrs G.H. Hughes, W.W. Hughes and C.M. Hughes enlisted and long ago left for the front. This week Mr. C.W. Hughes, the fourth son, enlisted at the local recruiting office, making, as we have said, a record for the district. They are all fine specimens of Australian manhood and when they get into holds with the Huns they can be relied upon to give a good account of themselves.”

His brothers George, William, and Charles had enlisted on 7 September 1915.

They were the sons of Arthur and Mary Hughes.

George Henry Hughes, the eldest of the brothers, departed Brisbane on active service on 31 January 1916 aboard HMAT Wandilla.

He had joined the 9th Reinforcements of the 26th Battalion but upon arrival in Alexandria, Egypt, he transferred to the newly formed 2nd Pioneer Battalion.

Attached to the 2nd Infantry Division, the 2nd Pioneers were tasked with light engineering works such as the construction of defensive positions but were also trained and fought as infantry.

On 26 March, George left Egypt aboard HMT Llandovery Castle bound for Marseilles, France, from where he travelled north to the fighting on the Western Front.

The Australian 2nd Division fought in the Battle of Pozieres in July and August 1916 and in the Second Battle of Bullecourt in May 1917.

In September 1917, the 2nd Pioneers were in position near Ypres, Belgium, where they supported the 2nd Infantry Division as it prepared for the Battle of Menin Road.

George died on 9 September after being wounded by fragments from a bomb dropped by a German aircraft.

William Walter Hughes was 23 years old when he departed for the war on 11 March 1916, and was the only brother to come back from the war without injury,

Charles Montease Hughes was 19 years old when he also joined the 15th Reinforcements of the 5th Light Horse Regiment. Charles and William had consecutive service numbers and left Australia together aboard HMAT Orsova. When they arrived in Egypt in July 1916, Charles joined his brother in 1st Field Squadron Engineers. However, on 5 August he was admitted to hospital with a serious knee injury which he apparently suffered when a horse fell on him. Charles’ knee injury could not be treated in Egypt, so he was sent back to Australia on 2 September. His knee injury did not respond to treatment, so on 22 November 1916, Charles was discharged from the Army as being medically unfit for further service.

He was determined to re-enlist and on 27 June 1917, an Army medical officer determined that he had recovered sufficiently from his injury to rejoin the Army. Charles re-enlisted in Brisbane on 12 December 1917, just three months after his brother George had been killed. Charles joined the Light Horse Reinforcements and left Sydney aboard SS Port Darwin on 30 April 1918 but had to disembark at Albany, Western Australia, because his knee injury flared again.

Claude joined the 22nd Reinforcements of the 9th Battalion and left Brisbane aboard HMAT Marathon on 27 October 1916. He arrived in England on 9 January 1917 and underwent further training until he left for the Western Front in May. He served with the 49th Battalion in France until wounded in action on 5 April 1918 at Dernancourt. Claude suffered a gunshot wound to the thigh and spent the next month in hospital. He rejoined his battalion but spent the last three months of 1918 in hospital in France suffering from seborrhoea, a chronic skin disorder. Claude returned to Australia from England on 9 February 1919. He was discharged as medically unfit in May 1919 due to an acute inflammation of the middle ear.

Another local boy, Patrick “Paddy” Hyde, died in action aged 29 at the Battle of Pozieres, six days after the death in the same battle of fellow Stanthorpe man Jack Swaysland.

1916 saw an important development for the region, with the Australian Goverment realising that when its army of servicemen had to return to civilian life, it was going to be a major undertaking to settle these men back into society.

So the Soldier Settlement Scheme was born, and areas of the Granite Belt became part of that scheme.

Thus, why looking at a map of the Granite Belt sometimes feels like looking at a map of France.

Also in 1916, the tin mining boom had lost its momentum and many in the region had turned to other incomes.

There were still large grazing properties in the district, which were to a great degree, as yet undeveloped. However, throughout the Granite Belt, and particularly within the proximity of the main Southern Railway line, orchards and farms had been established, and with a degree of success.

It was usual for a budding orchardist to supplement his income by growing vegetables until such time as his fruit trees came into full bearing.

Studies reportedly showed that 15 acres of land were sufficient to produce a good living.

In 1916, Mr Benson, the Director of Fruit Culture, came to Stanthorpe and inspected land at the Thirteen-Mile, (later Amiens) which had been set aside for settlement by returned soldiers.

At that time, fifteen thousand acres had been acquired, and surveyor Mr Jopp was given instructions that each block had to have at least fifteen acres of good orchard land.

To comply with this, the area of the blocks varied considerably at times.

Officially, it was declared that – “The public is assured that the soldiers would be placed on the land under such conditions that they could hardly help making a success of their undertaking”!

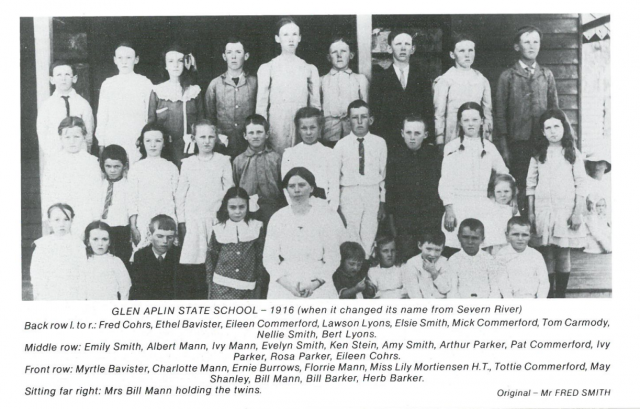

Also in 1916, the Severn River State School was renamed Glen Aplin State School.

It had been the Severn River School for the previous 28 years and on several sites.

Lily Mortiensen was the Glen Aplin School Head Teacher from 1 January 1916 to 16 August 1916, while Mary Gertrude Houston took over on 17 August 1916 and remained in the role until 22 June 1917.

39 students enrolled, including Henry Cohrs, May Sheila Stanley, Elsie Harriet Mann, and William Henry Mann.